Traditional Japanese Craftsmanship: Tatami in the 21st Century

An interview with award-winning tatami craftsman, Mitsuru Yokoyama

Tatami is a rush-covered straw mat used for flooring and dates back to the Nara Period when the word, tatami, first appeared in Kojiki, the oldest Japanese book written in 712. Originally a luxury item available only to the wealthy, tatami were thin handmade mats that could be rolled up or placed on top of wooden flooring for the highest aristocrats and nobles to use as seating. In the Muromachi Period (1336-1573), nobles started to spread and install tatami to cover entire floors, and these rooms became known as zashiki, measured by the number of tatami mats that could be configured to fit in a room. In the 16th century, Sen no Rikyu, the founding tea master in Japan, began incorporating tatami in tea rooms, and by the 17th century tatami was common-place and could be found in everyday homes. Even to this day regardless of whether a floor is wooden, carpeted or tatami, rooms in Japan, are measured by tatami fit — for example, “a 6-mat room.” In recent years, however, the demand for tatami has decreased as young people opt for easy-to-clean, modern flooring. Similar to other traditional Japanese crafts, the tatami industry is having to find ways to evolve and adjust to a new market.

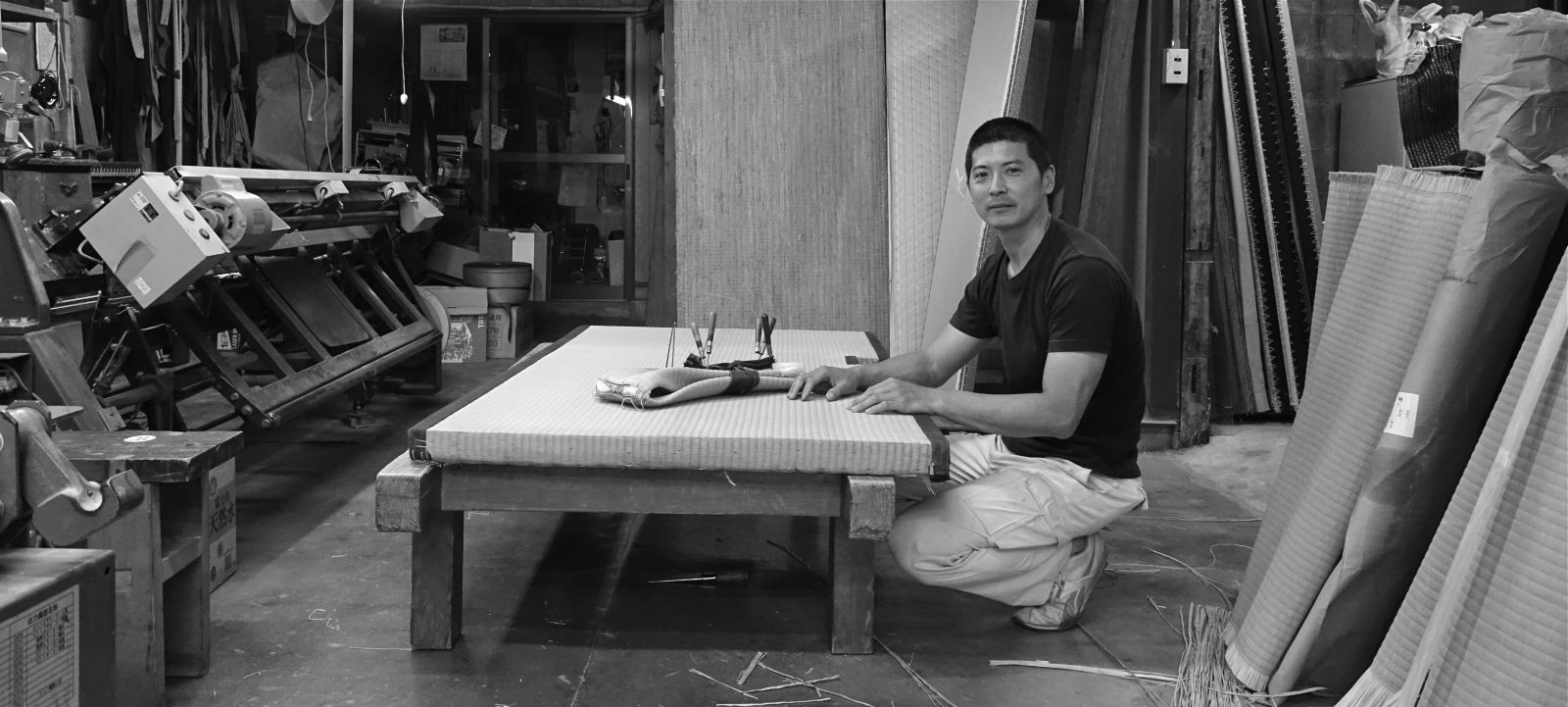

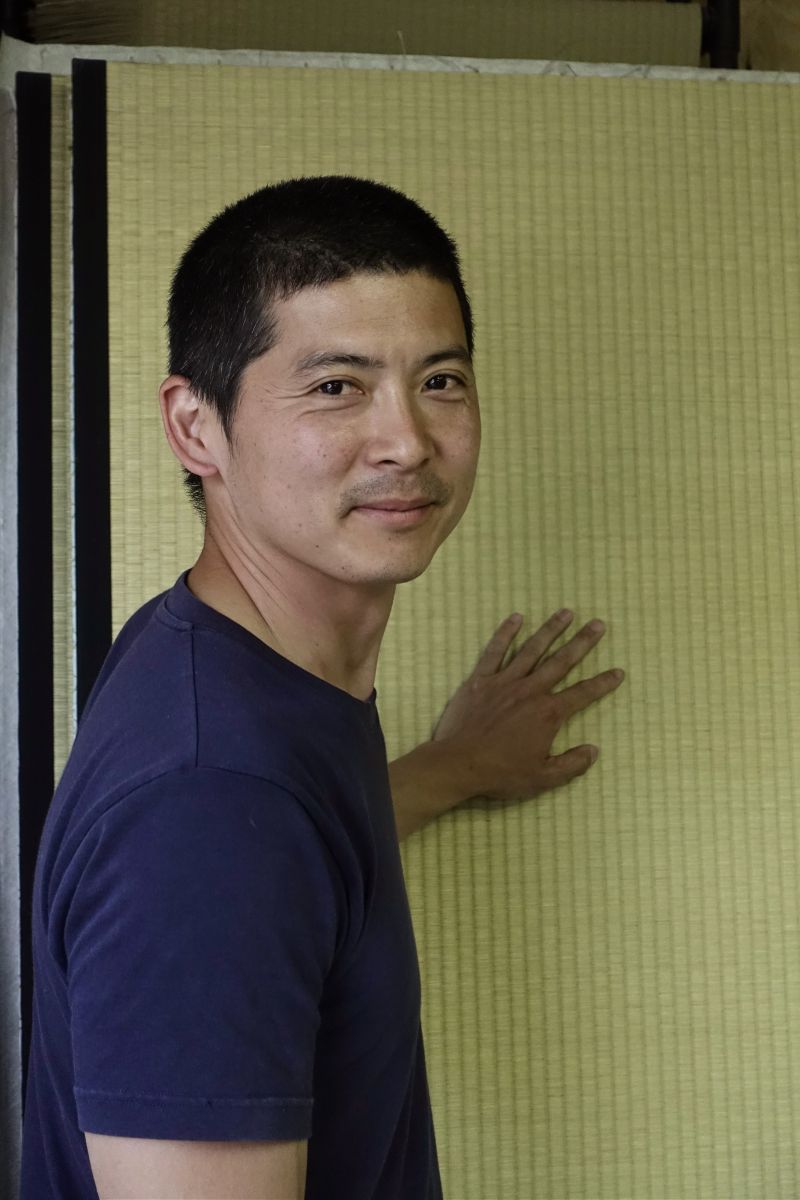

Mitsuru Yokoyama. Picture by Lisa Y Allen.

In 2016, Lisa Allen sat down with with award-winning tatami craftsman, Mitsuru Yokoyama. Over the past six years, Mr. Yokoyama has fine-tuned his craftsmanship at Motoyama Tatami in the Daitoku-ji Temple neighborhood, a fourth-generation-shop, which has been in business for over 100 years. Mr. Yokoyama works with the founder, Mr. Motoyama, and son, to provide and install tatami for temples and shrines in Kyoto as well as cater to an increasing demand for tatami abroad. Mr. Yokoyama is based in Kyoto with his wife and daughter.

Lisa Allen: How did you become a tatami shokunin (craftsman)?

Mitsuru Yokoyama: I was living in Australia and working as a boat builder for luxury yachts and catamarans. I liked it, but I knew it wasn’t something I would do long term. It’s a very challenging job — very dusty and the fiberglass destroy your lungs. I am married to an Australian woman so finding something unique and fulfilling long term in Australia was important for me. I thought a lot about how I wanted to make my mark and knew I’d like to pursue something related to my Japanese culture.

I spent a long time thinking about Japan, particularly the architecture and traditional arts such as ikebana (art of flower arrangement) and chanoyu (tea ceremony) — which use tatami. I wanted to create something that no-one else could in Australia. I missed aspects of Japanese life, and after living overseas for a long time, I wanted people outside of Japan to experience this beautiful part of my culture. Tatami is more than mere flooring, it is relevant to many aspects of Japanese life. Still today, tatami is a central and intrinsic aspect of ceremonies and architecture.

Back in the day, tatami shops only accepted people whose parents were in the tatami industry; the business and skill were inherited. Everyone involved was the son of a tatami craftsman. These days, fewer people are interested in learning about the traditions of tatami-making. When I decided to return to Kyoto and rigorously study tatami in school and as an apprentice, I was lucky to meet one of the kumiai (heads) of the organization. He liked my ideas and take on tatami, and connected me with a fourth generation tatami shop that is over 100 years old, which helped me to enter the industry. I've been a tatami craftsman for 6 years now, working on a wide variety of projects.

.jpg)

Men making tatami - late 19th century — Image: Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

LA: What makes a tatami well-made or beautiful?

MY: Tatami is made with igusa (rice straw). We buy the tatami omote (front side), which is the igusa prepared and woven by our partner farmers. The igusa isn't from the regular rice paddies you see, we have special farms in Japan that must adhere to very strict growing regulations. It’s one of the reasons why Japanese materials are more expensive and look different to the comparable Chinese product. My job is to stitch the tatami omote and base together — it’s a bit more complicated than that but basically that’s what I do.

.jpg)

Igusa. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

.jpg)

Lining up the extra igusa and heri. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

Heri. Picture by Lisa Y Allen.

It’s difficult to tell once the tatami is installed exactly how well-made it is. It’s more obvious when you reverse the tatami and examine the little details, like the stitches by the heri (edges). Are the stitches small and regular? Are the tatami omote and base well connected? Is the extra igusa that is used on the heri straight?

For the temples and tokonoma, it’s clear when the tatami doesn’t look right. Part of kamon (crest) on the edge might be cut off or the dimensions of the room might look off. For a tea room if the tatami is not aligned well, the hearth (opening for the teapot) will look strange. Before we install in a tea room, we must understand the rules of tea ceremony and consult the tea masters.

LA: How long does it take to make a standard tatami? How many do you make per week?

MY: There are two ways to make tatami — by machine, or by hand. Nowadays, tatami is almost all machine made. My shop installs tatami for Urasenke, World Heritage Sites, temples and international clients, all of whom want the highest quality and most traditionally-made tatami, which is lucky as it means I get to make much of the tatami we make in-store by hand. Recently I hand-made tatami for Daitokuji Temple and Ise Shrine. Tatami in apartments and ryokans are more often than not made by machine. Machine made tatami is still beautiful but it’s like anything, something made by hand has a certain energy and shows off the attention to small details.

Lining of Kamon. Picture by Lisa Allen

Ryōgen-in (龍源院), Daitoku-ji (大徳寺). Kyoto, Japan. Picture by 荻野 NAO之

On average, one handmade mat takes a full day to build and usually I have an assistant, while the machine made tatami is very quick and takes 30 minutes to complete. Therefore, handmade tatami is more expensive because it requires intensive labor and requires higher quality materials.

Last week I was busy and made almost 250 tatami. A ryokan (bed and breakfast) in Gion, Kyoto ordered 140 new machine-made tatami. Daitokuji Temple also ordered 12 handmade tatami. Tatami for temples generally have edges with kamon. The pattern has to be matched up exactly to create a flush circle where the mats join, which is tricky and takes time.

Ryōgen-in (龍源院), Daitoku-ji (大徳寺). Kyoto, Japan. Picture by 荻野 NAO之

There are three sizes of tatami:

1. Kyo-ma (Kyoto size): 191cm x 95.5cm

2. Kanto-ma or Edo-ma (Tokyo size): 176cm x 88cm

3. Chyukyo-ma (Nagoya size): 182cm x 91cm

Six Kyoto tatami equal nearly eight Tokyo tatami. Since I’m based in Kyoto, I mainly make Kyoto sized tatami. However, there is a growing trend of apartment buildings in Kyoto installing Tokyo-sized tatami mats.

During the Edo Period, the bushi (samurai) produced a lot of tatami. In Tokyo they decided to make the tatami a smaller size, so a larger number of tatami could be sold to consumers, and they could make more money. At least that’s one of the theories behind why Tokyo-ma is smaller.

The cost of tatami varies dramatically across the board. The average-machine built tatami costs ¥20,000 (about $200), while a standard handmade tatami is ¥100,000 or $1000. Handmade mats can go right up into a few thousand dollars depending on the materials. If a client wants to use top quality materials and have personalized edges then the tatami has to be produced by hand, otherwise it's not worth it as it wouldn't do the materials justice.

Although people may think they see tatami everywhere, few realize how many tatami businesses are struggling to stay open. There is a lot of competition from China making cheaper, lesser-quality omote. It’s a shame because I am interested in more traditional spaces that use high-quality materials.

LA: Why do you think tatami is an important feature of Japanese design?

MY: Tatami is natural; it’s part of a natural cycle that has been around for generations. Japanese people are born and die on tatami. It’s part of our lifestyle. One time I installed tatami into a woman's house, and she said, “I feel much more peaceful and relaxed.” The smell of brand new tatami is beautiful — it's like being in nature. Tatami works as an environmental agent in the home. It absorbs carbon-monoxide and regulates the temperature in a home by sucking the moisture out of the air when it’s humid, and releasing moisture when the atmosphere is dry. Some people are surprised, but because tatami is made from natural materials, it’s friendly to people and children who are allergy sensitive. Tatami is an experience of the senses with the natural smell, the cushiony feel underfoot, and its wabi sabi nature. It’s perfect for meditation.

LA: What is the most obscure or unique tatami you have made?

MY: The longest tatami I ever made was for Ise Shrine. It was a huge mat, two and a half tatami in length (approximately 4 meters) and it took three of us to carry it.

I was also asked to showcase an innovative type of tatami in the Futaba Aoi Festival, an event presenting works traditional Kyoto craftspeople at Kamigamo Shrine. I’m lucky to know another craftsman who makes zori (Japanese sandals). Through experimentation, he’s created incredible black igusa that I’ve started to make tatami with. It’s unique because while there are other black tatami mats on the market, none are made with as deep and luxuriously black igusa. For the showcase, I received a special red robuchi (hearth frame) from a tea master and hand-made the black tatami for a tea room. I don’t know how and if tea masters will accept black tatami, but these types of new ideas are necessary for the industry to survive.

Black Tatami for Futaba Aoi Festival. Picture by Mitsuru Yokoyama

Black Tatami featured in “ICHIMATSU” house by Fumiko Kaneko. Tatami by Mitsuru Yokoyama. Picture by 荻野 NAO之

LA: Who are your clients?

MY: At Motoyama Tatami, we continue to build our domestic and overseas client base. We have a new client in Israel who loves Japanese culture and wanted tatami installed in her bedroom, so I flew out there twice, first to take the different measurements for the room and then to install the tatami. We work in the U.S., Canada, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Australia, and parts of Europe.

Mitsuru Yokoyama at Motoyama Tatami. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

Mitsuru Yokoyama at Motoyama Tatami. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

Inside details of Motoyama Tatami. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

LA: What is the most important part of the tatami?

MY: A lot of people abroad think Japanese culture is about ninja and maiko (geisha), but I want to show people that the culture here is much more than that. Japanese people love the smell and feel of tatami. They feel comfortable and calm on tatami. It’s part of everyday life and it’s inherent to our culture.

It’s an honor and responsibility, and I feel excited when I make tatami, especially if it’s for a World Heritage Site. It’s so satisfying to install new tatami into a client’s room. Being open to new ideas is really important. Many people now like tatami in different styles; tatami with no edges or half-size tatami. It creates a minimalistic aesthetic. A good tatami craftsman is someone who pays attention to detail, is strong, careful, and open-minded to new ideas. For tatami to survive into my daughter’s generation, tatami has to appeal to young people and those overseas. That’s what I’m working on.

Mitsuru Yokoyama. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

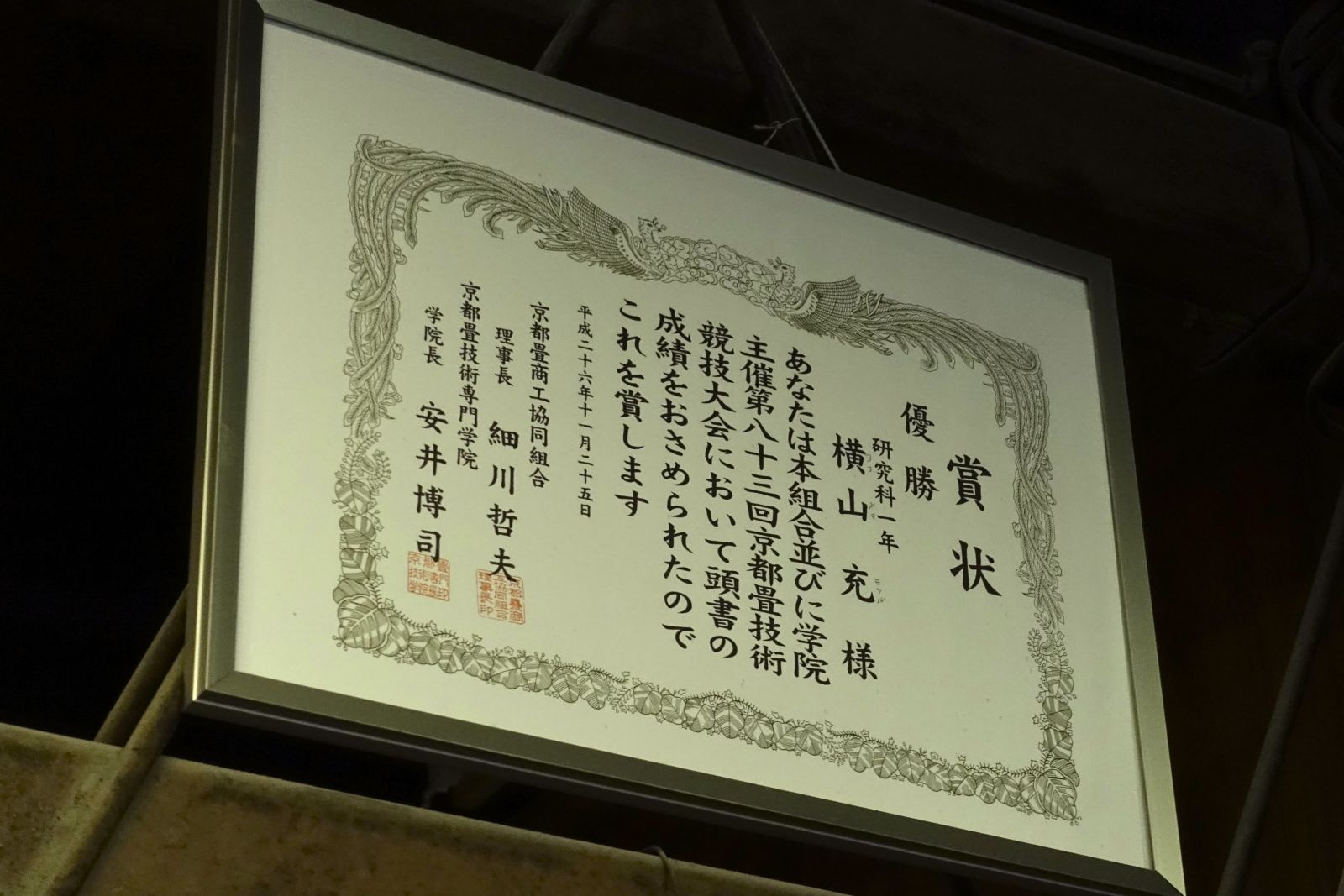

Mitsuru Yokoyama’s award from the Kyoto Tatami Makers Guild. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

Motoyama Tatami. Picture by Lisa Y Allen

Motoyama Tatami

45 Murasakino Monzencho,

Kita Ward, Kyoto

603-8216

075-491-8608

Lisa Yamashita Allen is a writer and photographer based between Washington, DC and Kyoto. She currently works at Meridian Hill Pictures, a documentary production company. You can read her previous article for ZenVita here: 10 Reasons to Live in a Japanese Style Machiya

If you are interested in adding a touch of Japanese style to your own home interior, take a look at our tatami mat room design ideas. ZenVita offers FREE advice and consultation with some of Japan's top architects and landscape designers on all your interior design or garden upgrade needs. If you need help with your own home improvement project, contact us directly for personalized assistance and further information on our services: Get in touch.

SEARCH

Recent blog posts

- November 16, 2017Akitoshi Ukai and the Geometry of Pragmatism

- October 08, 2017Ikebana: The Japanese “Way of the Flower”

- September 29, 2017Dai Nagasaka and the Comforts of Home

- September 10, 2017An Interview with Kaz Shigemitsu the Founder of ZenVita

- June 25, 2017Takeshi Hosaka and the Permeability of Landscape

get notified

about new articles

Join thousand of architectural lovers that are passionate about Japanese architecture