The Brilliant Folds of Akihisa Hirata

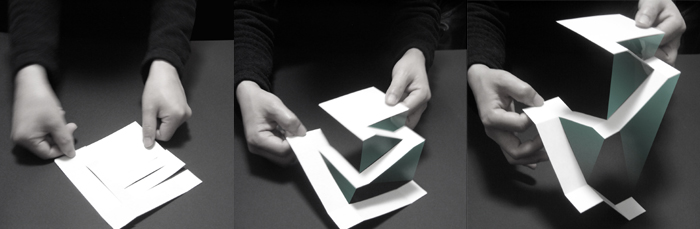

When thinking of Japanese architecture, the word ‘paper’ often comes to mind. We picture long and blemish-free white sheets of shoji on sliding doors, crisp and clean as if ironed. In the work of Akihisa Hirata we too see paper, but in his unique case, it presents as the delicately manipulated folds of origami. And the comparison with origami seems apt somehow, as what is architecture but the manipulation of forms, the manipulations of materials, the manipulation of landscape?

Akihisa Hirata

The formation of Hirata himself began in Kansai, where he was awarded the top award for his graduation design upon completing his graduate-level studies in architecture at Kyoto University,. Not long after, Hirata moved to Tokyo to begin an eight-year apprenticeship with Toyo Ito. During this time he participated in a number of renowned projects, including Ito’s Bruges Pavilion in Belgium and Tod’s Omotesando. These designs are quite reminiscent of Japanese kirigami paper cutouts, and from them, it is clear where Hirata found his inspiration.

TOD's Omotesando Building, Tokyo, (2004). Image by Flickr.com user "d'n'c" (CC BY-SA 2.0))

This inspiration is as philosophical as it is creative. Hirata feels that the more recent generation of architects have a more intellectual approach to Japanese design, one that lends itself to tangents into theory and elaborate explanation. Hirata prefers the work of his teacher Ito’s generation, a time of pioneers who were operating from a position of simple and solid principles. He claims that their work is instinctive, rather than cerebral.

r-minamiaoyama © akihisa hirata architecture office

Ironically enough many of Hirata’s designs remain on paper, and not having yet fully manifested themselves, remain in the realm of the intellectual.

That doesn’t mean his work hasn't gotten a great deal of attention. Two years after forming his Akihisa Hirata Architecture Office, he received the 2007 Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) New Architect Award. He has also won second Prize in the 2011 Kaohsiung Maritime Culture and Pop Music Center Competition in Taiwan, in which he envisioned the waterfront as the porous bubbles of sea foam. That same year he took another second prize for the New Kyoto Prefectural Library and Archives Competition. In 2012, Hirata was part of a Japan-team that won the Golden Lion at the 13th International Venice Biennale of Architecture, a prize shared with mentor Toyo Ito, Sou Fujimoto, and a number of other young architects.

r-minamiaoyama © akihisa hirata architecture office

A four-sided, perpendicular form such as paper lends itself to the formation of triangles, and as such most works of origami are triangular three-dimensional presentations of a single two dimensional sheet. Likewise, in Hirata’s designs, we see a large number of triangular pitches and gables rather than simple right angles, where the overall structure seems to be formed from a single compositional element. The recent (and admittedly controversial) Triangle of Life theory suggests that triangular spaces are far safer and much more stable in an earthquake, as triangles are the most common shape found in collapsed buildings. It is little surprise then that most of Hirata’s actualized designs are apartment buildings and shared living spaces, built in the days of stricter building codes imposed after the devastating 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Similarly, he has been active in the rebuilding of those areas most stricken by that disaster.

Architecture in 20th Century Japan saw a movement away from the simple paper and wood materials that proved all too vulnerable in the fire bombings of the Second World War. The 2011 earthquake and tsunami is quickly proving to be another watershed event in architecture, and stricter building codes require a reevaluation of material and forms. This is the perfect stage upon which Akihisa Hirata is hoping to make his mark, and innovate new principles in the manner of those architectural giants of the post-war era. Although Hirata still has relatively few projects to his name, it is a name already being written on the clean white pages that have quickly become his trademark.

Edward J. Taylor is a writer and editor based in Kyoto, Japan. Previously he has written for ZenVita on the architecture of Kenzō Tange, Kengo Kuma, Shigeru Ban, Kazuyo Sejima, and Toyo Ito.

For more innovative designs from Japanese architects visit the ZenVita Projects page. ZenVita offers FREE advice and consultation with some of Japan's top architects and landscape designers on all your interior design or garden upgrade needs. If you need help with your own home improvement project, contact us directly for personalized assistance and further information on our services: Get in touch.

SEARCH

Recent blog posts

- November 16, 2017Akitoshi Ukai and the Geometry of Pragmatism

- October 08, 2017Ikebana: The Japanese “Way of the Flower”

- September 29, 2017Dai Nagasaka and the Comforts of Home

- September 10, 2017An Interview with Kaz Shigemitsu the Founder of ZenVita

- June 25, 2017Takeshi Hosaka and the Permeability of Landscape

get notified

about new articles

Join thousand of architectural lovers that are passionate about Japanese architecture