The Omiya Bonsai Art Museum: A Visit

Image courtesy of the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum

Bonsai (“potted planting”) is one of the most recognizable aspects of Nihon-no-Bunka. It is easily transportable and has played a key role in the dissemination of Nihon-no-Bunka worldwide. It has its own section in the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. Many of the samples in that collection are produced by members of the royal families of Southeast Asia, attesting to its prestige as well as its popularity. It identified Pat Noriyuki Morita as “Japanese” in the opening scenes of The Karate Kid.

However, bonsai viewings in the country of origin were until recently primarily in non-museum settings: specialty garden centers, markets at shrines or temples, or regional hobby clubs at private residences or community centers. A private art collection may have included some specimens. The rise of international plant branding through the consolidation of the breeding industry worldwide has created both the opportunity and need for bonsai organization and promotion. This, plus the current trend of marketing Nihon-no-Bunka, has led to the opening of the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum, the first public art museum dedicated solely to bonsai.

Located in the Bonsai Township (bonsai-cho) area of Saitama City, the area surrounding the Museum was originally called Bonsai Village (bonsai-mura) and has an interesting history. Originally, uekiya landscape gardeners were clustered in Bunkyô Ward, Tokyo. They developed bonsai in the mid-19th century and these were preferred among the new political classes. Being easy to take care of, bonsai could demonstrate a politician’s appreciation of “traditional culture” while the country reestablished itself as a Western-style nation. Bonsai could be displayed both in Japanese- and Western-style homes. After being displaced by the Tokyo Earthquake, many in the trade moved en masse to the current location. In 1928 a local union was founded and by 1936, 35 nurseries were established (at present, there are six still in the area). This history is a draw to the area and the museum was established in 2010 to disseminate interest worldwide; the repaneled Omiya Kôen Station even smells like cedar. One section of the station displays a Bonsai Village Walking Route leading to the museum behind the station.

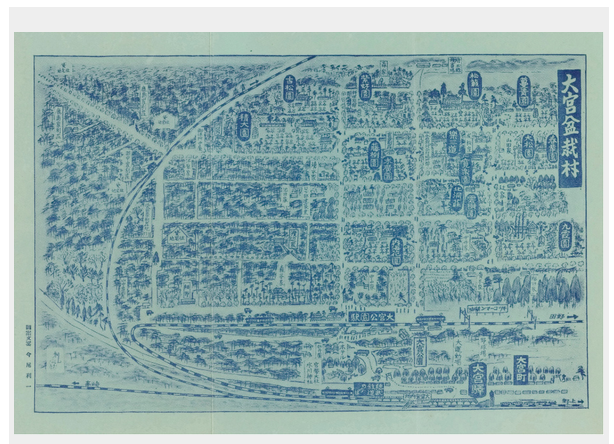

A contemporary map of Bonsai Mura from the 1930's showing the train line and bonsai traders. Many are now private residences. Image courtesy of Omiya Bonsai Art Museum.

One portion of the route includes Kaede Dôri. This is an attractively paved walkway well-shaded and lined by very well-appointed houses. According to a museum map, some of these properties were formerly nursery businesses. A few of these remain, including the old union community center containing a stile commemorating the founding of the village.

The museum is a two-story municipal building in an airy and traditional design meant equally to instruct and display. The wide entrance hall leads to a passageway lined with explanatory signs in Nihongo and English. The first sign explains how to look at bonsai, starting with the roots, then up through the trunk to the branches and leaves. Roots should be at least partly visible. Branches should be balanced and free of rot. However, there is an aesthetic of decay known as jin (神) for branches and shari (舎利) for the trunk. These terms describe the technique of exposing the white, dried sections of dead wood in a still-living bonsai. Jin means god and shari has the double meaning of the remaining bones following cremation and, occasionally, white rice. These terms are indicative of “left behind” existentialism often expressed in personal narratives as iki-nokori, literally “left behind with life”.

Bonsai pine in museum entrance with large shari trunk. Image by Adam Lebowitz.

Next, signs explain the different bonsai “poses”: trunks are straight chokkan, or curved môyôji, wind-swept fuki-nagashi or cascading over kengai. A large touchscreen at the end of the hallway displays the entire collection which includes pots, display tables, rocks, and printed material. Photos show the bonsai in different seasons. If bonsai (along with ikebana flower arranging) is the original installation art it is uniquely non-static. Leaves turn colors and drop, fruit and flowers bloom. The “art” aspect of bonsai is demonstrated by the largest interior display of alcoves: Gyô-no-Ma, Sô-no-Ma, Shin-no-Ma. Gyô-no-Ma tends to be strict, severe, and open, while Sô-no-Ma is more flexible and allows for partitions. Shin-no-Ma is a fusion of the two and also the most opulent.

The path then leads outdoors (with complementary umbrellas) around a central pond area to a full-fledged teien garden display. It is a very pleasant and quiet area of town and a popular date spot; young and old couples, some families, a few children. Standing to the side like a boss sentry is the Chiyoda Pine, 1.6 meters high and 1.8 meters wide. Largest in the collection with exposed roots and moss, it looms imperiously over its other brethren like a well-behaved pit-bull ready to pounce if one leaf or needle gets out of line. This bonsai has personality. A small museum beside the garden houses a small collection of scrolls and historical material tracing the development of bonsai from its roots in the elite classes of the Muromachi Period to becoming popular culture during the Meiji Period, and now its modern appreciation as art.

A view of the teien garden from the 2nd floor balcony. The Chiyoda Pine is on the far right. Image by Adam Lebowitz.

Bonsai are a foil to modern leisure culture that is digitalized, informationalized, overly self-conscious and self-reflective. They are a respite for the creator and the viewer, and like shodô calligraphy become more interesting with the age and skill of the producer. This museum is definitely recommended as an introduction. The location is an added bonus that does much to explain the origins and social context. Audio guides in Nihongo, English, Korean, and Chinese are available. There is a museum shop, a small outdoor market beside the parking area, and a schedule of workshops and lectures for those wanting to learn more. The museum website has information on bonsai markets in the area.

.jpg)

Omiya Bonsai will soon be available from the ZenVita online store. Image courtesy of Omiya Bonsai.

Omiya Bonsai produces the world's leading bonsai brands and from this summer these will be exclusively available from the ZenVita online store. We ship internationally to more than 50 countries worldwide. If you would like to receive more information about the online shop and special offers on bonsai then please SIGN UP from HERE.

SEARCH

Recent blog posts

- November 16, 2017Akitoshi Ukai and the Geometry of Pragmatism

- October 08, 2017Ikebana: The Japanese “Way of the Flower”

- September 29, 2017Dai Nagasaka and the Comforts of Home

- September 10, 2017An Interview with Kaz Shigemitsu the Founder of ZenVita

- June 25, 2017Takeshi Hosaka and the Permeability of Landscape

get notified

about new articles

Join thousand of architectural lovers that are passionate about Japanese architecture