SHIGEMORI MIREI AND THE POWER OF ROCK

Tofuku-ji Abbots Quarters North Garden by Shigemori Mirei; Picture by John Dougill

Rocks in Japan have long been seen as sacred. In Shinto there are ‘spirit-bodies’ made of rock which form the object of worship, the idea being that ancestral spirits descend into them and are made manifest. These special rocks, known as iwakura, are hung with rice rope and treated with reverence. In Buddhism too rocks are revered, and all over Japan are bibbed stones representing Jizo, guardian of the dead.

The association with the dead is typical of an animist universe in which rocks represent continuity, in contrast to the transient world of vegetation. The desire for life after death means that the human spirit is associated with the former, the human body with the latter. The connections were reinforced by ancient burial patterns, when bodies were sealed in tombs (or left on hillsides). While the body decayed, the spirit was absorbed into the rock.

Some see these numinous rocks as the origin of Japanese gardens, for they were marked off as distinct from the surrounding nature. The ground around them may have been cleared, and as time passed other rocks were added and arranged in groups. The placement was done with care, for these were the seat of spirits. As Alan Watts pointed out, rocks are not dead and inorganic but foster life, the supreme example being the large rock on which we hurtle through space and which ‘peopled’ us into existence. ‘Where there are rocks, watch out!’ said Watts.

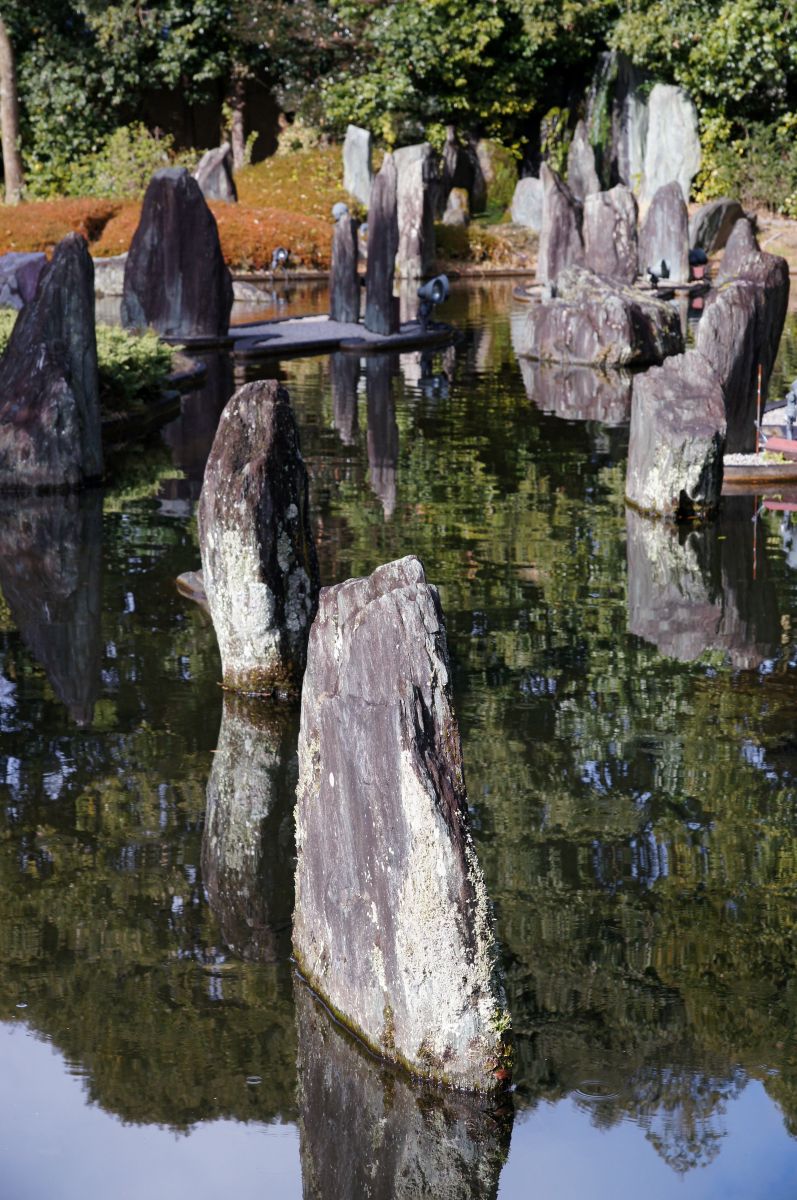

Horai Garden at Matsunoo-Taisha, Kyoto designed by Shigemori Mirei; picture by CC BY 2.5

One person very much aware of the potency of rocks was the twentieth-century garden designer, Shigemori Mirei ((1896-1975). He was a follower of Shinto, and the house in which he lived near Kyoto University had belonged to a line of priests from nearby Yoshida Jinja. ‘Nature is a world made by the gods,’ he once wrote, and in an essay on the Japanese garden he identified nature worship as the source. Interestingly, his trademark feature is standing stones.

As a young man Shigemori compiled a 26 volume series on Japanese gardens, and he used his knowledge of tradition in designing his own. Over 200 in all, the vast majority are dry landscape gardens (known as karesansui), often associated with Zen. Minimalist and sparse, the gardens only require rocks, sand (or pebbles) and a touch of moss. The raked gravel speaks of the flow of water, in which case the rocks represent islands. Or the raked gravel can suggest the endless flow of time, in which case the rocks might constitute ‘spots’ of existence. In either case the onlooker can sit, contemplate and transcend the mundane.

The spirituality is underscored by the symbolism. Typically there is reference to Mt Horai, the mountain that in Chinese mythology dominates the four Islands of the Blessed where the Immortals live. The utopia is a meeting place of human and heavenly worlds where opposites are brought together, signifying the underlying oneness of things. For the onlooker it provides a focal point for contemplation.

The unity is manifest in the Horai garden by Turtle and Crane Islands (emblems of longevity and good fortune). While the turtle can plunge to the depths, the crane can soar to the heights, and in their coming together the world of division is symbolically transcended. In pond gardens such islands are clearly identifiable; in dry landscapes they are often reduced to a simple yin-yang pairing of rocks, one vertical and one horizontal.

Along with the spiritual dimension is the aesthetic. ‘In order to contemplate the beauty of a Japanese garden, it is necessary to understand the beauty of stones,’ wrote Lafcadio Hearn. ‘Until you feel, and keenly feel, that stones have character, that stones have tones and values, the whole artistic meaning of a Japanese garden cannot be revealed to you.’

In creating his twentieth-century gardens, Shigemori built on the past, but at the same time he wanted to invigorate what he saw as a static tradition. ‘The old is new,’ was one of his guiding phrases, and by tapping into ancient wisdom in Jomon and Yayoi times, he sought to give his gardens a Picasso-like twist. You can see it in the coloured sand he used; the tiled borders; square-shaped azalea bushes; ‘unnatural’ straight lines and grids. For lovers of tradition these were a shocking violation of convention; for Shigemori they were ‘eternal modern’.

Tofuku-ji Abbots Quarters South Garden; Picture by John Dougill

Shigemori’s most famous work is his first commission at Tofuku-ji, where he laid out gardens on all four sides of the Abbot’s Quarters. To the right as one enters is a seemingly nondescript dry landscape with pillars in place of rocks. Look more closely, and one sees the pillars are positioned in the form of Ursa Major, a sacred constellation in Daoism. The pillars are recycled from the original temple, opening up dimensions of time as well as space. Yet beyond this is another level to do with Ursa Major’s everyday name of Big Dipper. Since the shape resembles the dipper used at Japanese water basins, the implication is that the garden serves as a form of purification for visitors.

The Cross at Zuiho-in, Picture by John Dougill

In a Shigemori garden there is always more than meets the eye, and the coded messages are nowhere more apparent than at Zuiho-in, a subtemple of Daitoku-ji. What looks like ordinary stones in a dry landscape turns out to conceal the modernist layout of a cross, only visible from a certain vantage spot. Precisely behind that spot is a stone lantern with a Maria at its base, as was the practice of Hidden Christians. The reference is to the temple founder, Otomo Sorin, who in later life converted to Christianity prior to an age of persecution when those following the religion went into hiding.

Reiun-in main garden with central plinth; Picture by John Dougill

Let us finish with a look at Reiun-in, a subtemple of Tofuku-ji. Here Shigemori’s garden features a representation of Mt Sumeru at the heart of Buddhist cosmology. Dramatic swirling waves of deeply raked sand encircle the centrepiece, which consists of a plinth bearing a precious historical rock. It seems like a pleasant piece of whimsy, until one considers the significance of a rock at the centre of the universe. ‘Even the most ordinary pebble has the history of this heavenly body we call earth written on it,’ says the geologist in Okuizumi Hikaru’s The Stones Cry Out. ‘All matter is part of an unending cycle... [Each rock is] a condensed history of the universe and keeps the eternal cycle of matter locked in its ephemeral form.’

Now there’s something on which to meditate.

The Shigemori Mirei Memorial Garden in Kyoto by his grandson Shigemori Chisao

John Dougill runs the Writers in Kyoto group and keeps a blog called Green Shinto. He teaches British Culture at Ryukoku University, and has written Kyoto: A Cultural History and In Search of Japan's Hidden Christians amongst other books.

Shigemori Mirei's grandson Shigemori Chisao has continued the family gardening tradition, and is now one of the most renowned landscape architects in Japan today. We are proud to say he is also a ZenVita associate designer. If you are interested in having a garden designed by Shigemori Chisao, please contact us for free advice and consultation: Get in touch.

SEARCH

Recent blog posts

- November 16, 2017Akitoshi Ukai and the Geometry of Pragmatism

- October 08, 2017Ikebana: The Japanese “Way of the Flower”

- September 29, 2017Dai Nagasaka and the Comforts of Home

- September 10, 2017An Interview with Kaz Shigemitsu the Founder of ZenVita

- June 25, 2017Takeshi Hosaka and the Permeability of Landscape

get notified

about new articles

Join thousand of architectural lovers that are passionate about Japanese architecture